Belonging

People have a need for belonging, which they seek in various groups in order to find social support and acceptance there. Support and acceptance are important for every individual and contribute significantly to well-being. However, it makes a difference whether membership in a group is self-selected or whether this group membership is imposed by society – without any action on the part of the individual. In this case, a sense of belonging can also be destructive. The flip side of belonging is comparable to a loss track. Group memberships are constructed only through demarcations, as the Robbers Cave experiment by the social psychologist Muzafer Sherif (1906-1988) showed:

The study served the purpose of conflict research. In the summer of 1954, eleven-year-old boys with almost identical social backgrounds moved to a summer camp in Robbers Cave State Park in Oklahoma, USA. There, without the boys’ knowledge, their behavior was observed and influenced for three weeks by researchers masquerading as camp staff.

From the beginning, the researchers formed two randomly selected groups that initially knew nothing about each other. After a few days, social patterns, hierarchies, and friendships had already formed in each of the two groups of eleven. The formation of this group structure marks the first phase of the experiment. In the second phase, the scientists made the two groups aware of each other and set them against each other with the help of sporting competitions. In the third phase, the conflicts that arose were to be resolved. It is interesting that in phase two the inner cohesion of the group grew, while more and more aggression against “the others” developed, they were insulted and belittled.

In order to feel they belonged to each other and, more importantly, to distinguish themselves from the others, the boys suddenly gave themselves group names, something they had not previously considered necessary. Thus, they needed categorizations to form their identities and make them tangible. In doing so, the boys developed opposing identities to distinguish themselves from one another, not because they had opposing ideas of norms. They even made flags with their own emblems and each developed their own rituals. As the second phase of the experiment progressed, assaults also occurred. The boys broke into the other group’s camp and vandalized it, and so on. They even armed themselves with baseball bats to fight each other. At this moment, the researchers initiated phase three of the experiment: reconciliation. By now, the groups were so at odds that they no longer wanted to talk to each other. To bring the boys back together, the researchers had two options: Either they established a new and, above all, common image of the enemy, or they set the two groups tasks that they could only solve together. The second option was chosen. These tasks included, for example, repairing the drinking water pipe, for which the boys first had to find the damage and then lend each other tools to fix it.

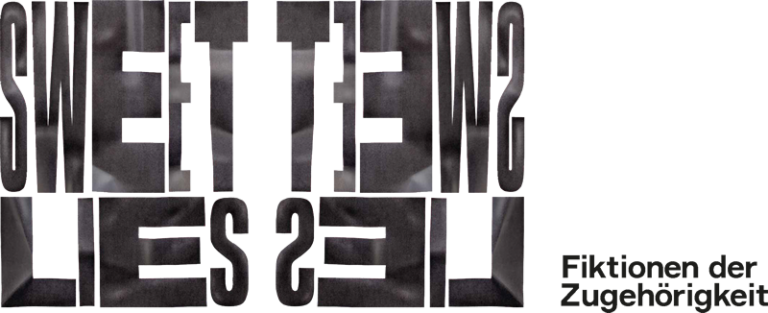

Sherif recognized in this experiment, first and foremost, that social groups develop their own structures, values, and rituals in a short period of time. They do this in order to be able to distinguish the members of their group from outsiders. These differences are usually the reasons for hostility between different social groups. However, they can be overcome by common goals, such as a paradigm shift. Repeats of this experiment with other protagonists in other cultures also produced the same results. Sherif’s experiment is thus one of the classics in psychology today. There is hardly any doubt left about the peace-promoting effect of superordinate goals. The behaviors revealed by Sherif can be applied to all identity categories. Thus, belonging becomes a fictional construct.