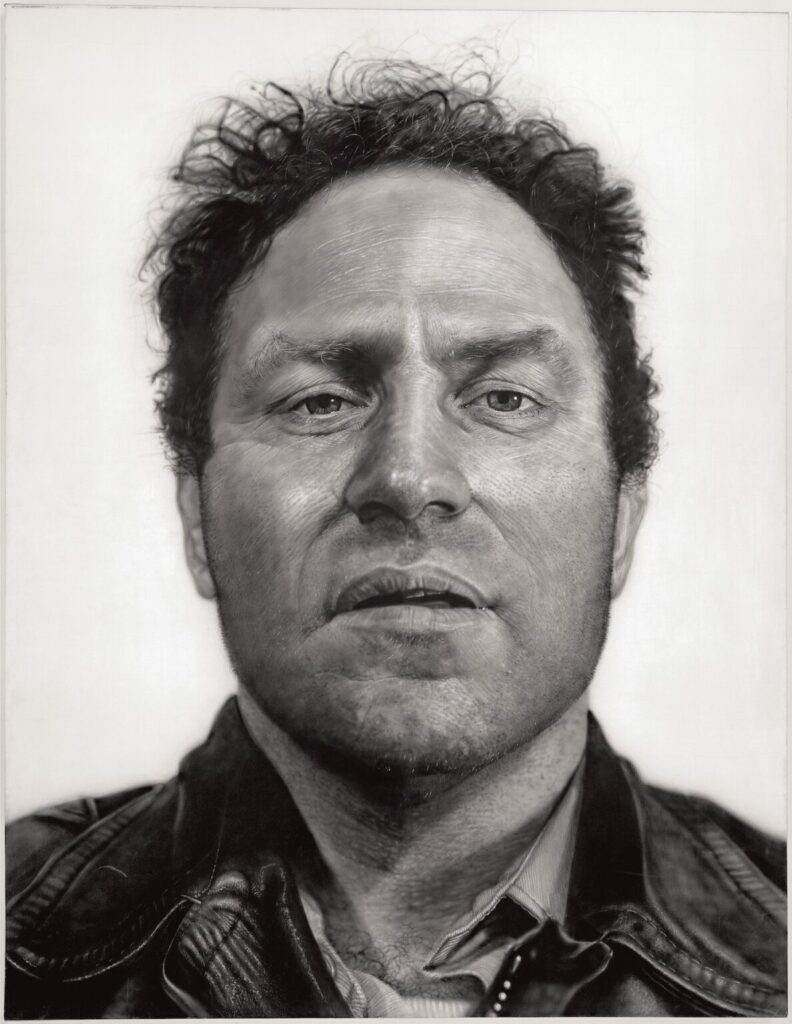

Chuck Close

* 1940 in Monroe (WA), USA

† 2021 in Oceanside (NY), USA

Nothing remains hidden from the eye of painter Chuck Close: no wrinkle that he does not capture on canvas. But how? Since the end of the 1960s, this form of photorealism has become characteristic for Close. The painter meticulously describes the faces of the portrayed, mostly close friends or family members, and depicts them in survival size, emotionless and usually frontal. Each time he uses a photograph as a basis, which he divides into individual plots with the help of a grid system, and then transfers them to the canvas. He himself says: “If the whole thing overwhelms you, if you don’t know how to depict the nose, you just have to leave it alone. Then you have to reduce the nose to a hundred little individual particles and solve the representation of first one particle, then the other, in turn, without giving it much thought, and in the end you have the nose.” Chuck Close has rarely moved away from this process in the last 50 years. In addition, the combination of photography and painting results in a precise enlargement of a portrait, which, with the help of painting, exceeded the technical possibilities of photography at the time: his paintings were thus not only pure imitations of the photograph, but even more exact than the photographic model, which is evident, for example, in the coarse-pored skin. Richard is one of the best known and earliest examples of this. Here is the en face depiction of Close’s fellow artist and fellow student, the sculptor Richard Serra.

Richard looks at the viewer with a cool and almost challenging gaze. The painting is one of the first that Close painted without a brush or in many colors, but with the help of a spray gun and the restriction to Black and White and its shades. Close thus attempts to bring out the individuality of a person. However, this is not done through attributes or symbols that are supposed to convey a person’s character in the form of a psychoanalytical representation, but rather through the precise observation and documentation of outward appearance. Close sees in the portraits landscapes of experience, in which each face tells its own distinctive story.

Chuck Close always remained committed to the painterly genre of the portrait. Even when he suffered a serious illness in 1988 that paralyzed his right side and almost meant the end of his career as an artist. Since then, he has worked with the help of a wrist cuff that holds the painting utensils and a lifting platform that helps the artist reach every spot on the larger-than-life canvases. Things only got quieter for Close after he was accused of sexual misconduct in 2017 in the form of verbally sexually charged slurs toward two models during a photo session in his studio. This was followed by a public apology from the painter. His career has not been able to fully recover since then, and several planned exhibitions have been canceled or postponed indefinitely. But what does the art business achieve with this form of self-censorship?

Those who undo pictures avoid discussion about them and their creators. This negates a reality that has led to the success of unequal distribution of power and various forms of discrimination in the past. One gives up the possibility of exposing and questioning these power structures. But this can also be the task of a museum: to stimulate thinking and debate.

in dialogue with

Megan Rooney

Old baggy root, 2018–2020