Theresa Weber

* 1996 in Dusseldorf, Germany

lives and works ibid

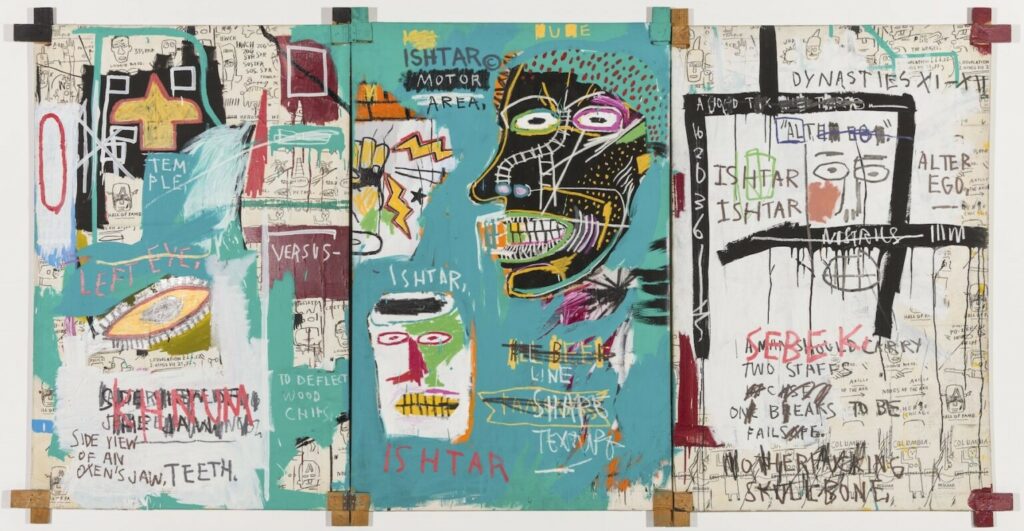

Theresa Weber often works with expansive installations in which she links her biography with current social discourses and makes them accessible by means of historical or mythological concepts. In response to Jean-Michel Basquiat‘s triptych Ishtar, Weber designed three altars as well as a wallpaper that mirror the triad of Basquiat’s work on the level of content and form. The figure of Ishtar fascinates the young artist, as the deity appears as a complex mythological figure, almost ambivalent in its connotations (deity of love and war, appearing in the body of a man or a woman), on which current questions about Identities can be based. The altars follow the same formal structure: Polyester resin plates lie on metal frames. Into these plates the artist poured so-called Woven Memories, mementos in the form of materials assembled in collage-like fashion. The hairpieces, lion images, body casts, and more composed in this way become topographical-looking archival materials that tell stories – of Belonging, Intersectionality, Black identities, ideals of beauty, feminism, Gender, and cultural hybridization. The translucent polyester resin, which has been provided with color pigments, repeatedly gives the impression of a fluid material when viewed, thus directly relating to the processual character of identity formations.

With Ishtar Gate, Weber explores, among other things, the question of today’s repositories of cultural artifacts from all over the world. Her point of departure is the Ishtar Gate of the same name in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, to which the blue tiles in Weber’s work allude. The Berlin Ishtar Gate in its present appearance is the result of a reconstruction with finds from an excavation around 1900 by the German Orient Society. The latter transported the recovered brick fragments to the capital of the former German Empire, where the Berlin Ishtar Gate was presented to the public for the first time in 1930. Against the backdrop of the debate on the return of cultural objects illegally acquired through robbery or fraud, demands to return these objects – now preserved in European museums – to their countries of origin have been voiced with increasing frequency in recent years. The Iraqi government, for example, has already demanded the return of the Berlin Ishtar Gate on several occasions. Weber is interested in the still unevenly balanced distribution of power in a postcolonial world that makes Germany reject these demands. At the same time, Weber’s lions, which are cast into the polyester resin and appear slightly transparent, refer to the iconography of Ishtar, the ornamentation of Berlin’s Ishtar Gate, and to Rastafarian Resilience in Babylon. Here Weber designs a system of symbols with multiple connotations, which can be formally ascertained in the multi-headedness of the lions.

The second altar deals with forms of representation of female ideals of beauty, which are particularly important in the Caribbean and the African diaspora. In this altar, Weber works with orthetic elements, i.e. elements that serve as extensions of the body, such as synthetic hair or artificial fingernails. These body extensions are part of a specific tradition; the braided hair in particular bears witness – often still today – to the fact that the artist belongs to the African diaspora. At the same time, Weber also raises questions about Cultural Appropriation, as such braided hairstyles (e.g., braids) have been worn again and again by White people in recent years. The use of artificial fingernails in the work reveals different readings: in the Caribbean, long nails are often considered a sign of emancipation from physical labor and thus of belonging to a higher social class, and are thus associated with prestige for the wearers. In contrast, in the Global North it is still often the case that women who stand for equality deliberately do without long fingernails so that they do not get in the way of physical work. At the same time, it can be observed that a new attitude toward these markers, which are read as feminine, is establishing itself in the generation of young women in the Global North: The open display of particularly feminine attributes is read as feminist empowerment, which reveals new forms of self-confidence.

The third altar deals with transformation processes of bodies and their images. With the help of body molds and pads as well as objects borrowed from strip and pop culture, Weber examines ideals of beauty on the one hand and relates them to the deity Ishtar on the other. For the four successive impressions of upper bodies made of translucent silicone are of men and women, but at first glance they cannot be read as clearly gender-specific. In this way, Weber leans on the current gender discourse against the backdrop of Ishtar’s mutability, who’s able to appear as a man or as a woman and – according to today’s understanding – could be called genderqueer. In addition, the artist infuses her work with hip, butt, and breast pads that shape the silhouette of a person, usually a woman, according to current ideals of beauty. By revealing the constructions of these body images, the viewer creates a distance to the objectively perceived body. On the one hand, the striving for an ideal form of one’s own body can be very stressful, but at the same time it is possible that a “positive fetishization,” as Weber says, takes place: if one appropriates these body images, critically questions them, and uses them for empowerment and emancipation. The artist sees the first signs of this in current trends in strip and pop culture, as indicated by the sequined pasties.

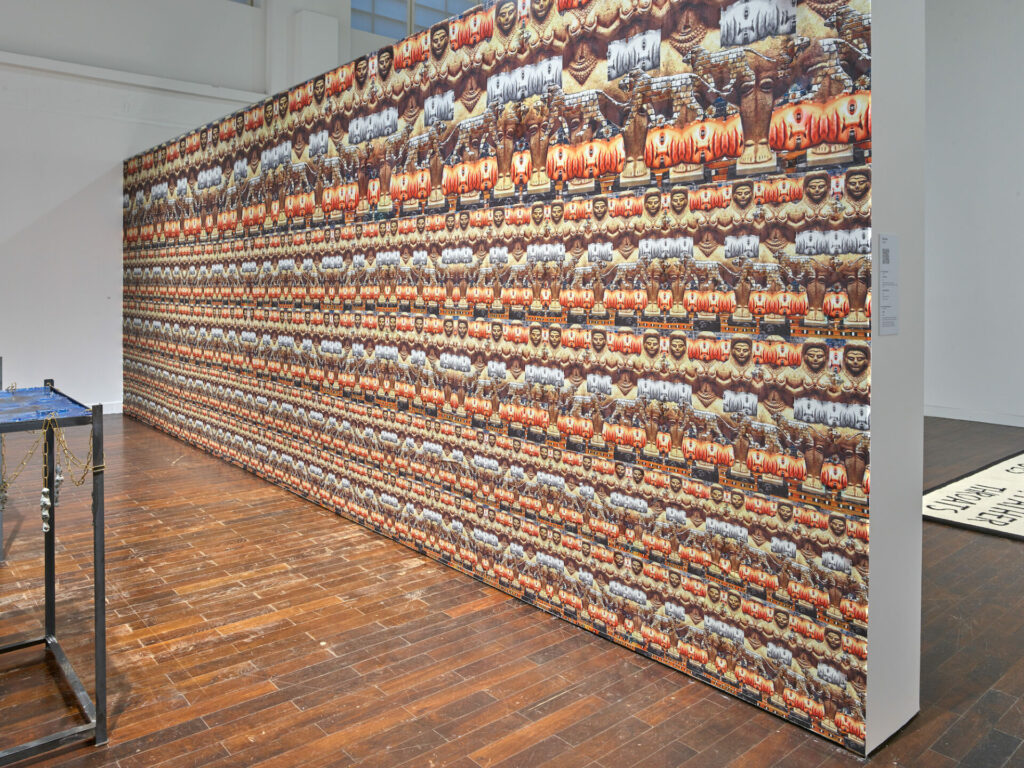

The wallpaper created by Weber is based as much on the rhythmic triad of Basquiat’s painting as on the artist’s three altars. Thus, the wallpaper is arranged in three horizontal panels whose motifs merge into a recurring pattern and taper towards the floor. On view here is an ancient stone sculpture of the deity Ishtar, showing her ambivalent physicality. Between the heads of the multiplied Ishtar figure, the alienated face of the artist appears again and again. However, this is to be read less as a self-portrait than as a transformation of the outer figure into a mask-like form created through an Instagram filter, which works with alienation effects such as the reflection of nose and mouth. The space between the faces is occupied by the blue tiles of the Ishtar Gate, a reference also found in the lower boundary of each of the panels in the form of the striding lions. Thus, the wall work reflects all the themes of the altars, interweaving the various focal points set by the artist, similar to the check patterns of textile works. This illustrates that the themes discussed should not be understood individually, but rather as a mutually dependent system.

With Ishtar Altars and Ishtar Wallpaper, Weber creates works that consider contemporary elements and discourses. At the same time, they testify to a great sensitivity in dealing with the past as well as individual and collective identity-forming characteristics. In this way, Weber is able to establish connections between past cultures and present power relations, which she reflects upon. In doing so, she repeatedly returns to her role as a Black artist within the operating system of art. Just like Basquiat, Weber designs a complex system of references consisting of collages, symbols, and motifs that allow viewers to enter into dialogue with unambiguous references as well as with open spaces of association. The visualization of the interactions between society, history, and pop culture unites Basquiat’s and Weber’s works, which thus reveal subtle connections.

in dialogue with

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Ishtar, 1983